- HOME

- Marketing

- Developing a Powerful Brand Positioning Strategy

- Coming Up with Your Company's USP and Value Proposition

Coming Up with Your Company's USP and Value Proposition

- 12 Mins Read

- Posted on December 3, 2018

- Last Updated on October 8, 2024

- By Lauren

In the last section, we guided you through the process of writing your company’s mission, vision, and values statements. These are essential documents because they articulate your company’s convictions about what an ideal world would look like and what core beliefs and behaviors will ultimately lead you to that place. In fact, if you’re having difficulty articulating your messaging, it may be because you don’t have that “core identity” in place yet.

But there are two other pieces you’ll want to have in place before you sit down to draft your brand positioning statement: your unique selling proposition (USP) and your value proposition.

While mission, vision and values statements are typically available to your prospects and customers, their primary purpose is to serve as a strategic guidepost for your team, so they know what to prioritize with every decision and customer interaction. Your USP and value proposition, on the other hand, will speak directly to your target market—in their language, about their problems. Indeed, these two messages combined are the most significant tools you have to explain to your market why they should do business with you—using terms that are relevant to them.

Will Swayne, the Managing Director of Marketing Results, recently wrote about his experience of talking to 165 business owners at an online marketing seminar, and discovering that fewer than 10 of those 165 were able to articulate what their USP was. However, as Swayne noted, all of those owners were able to answer the fundamental questions that would allow them to develop a USP (their strengths and weaknesses, their competitors’ strengths and weaknesses, their target customer). Of course, it’s one thing to know the answers to these questions yourself, and another thing to ensure your target market knows why you’re worth their time.

So let’s dive in. Even if you haven’t written a USP or value proposition yet, we bet you have the knowledge at hand to do so.

What’s the Difference Between a USP and a Value Proposition?

USPs and value propositions often get confused (or conflated) because both fall under the umbrella of “things we hope to communicate to our market.” But they serve different functions—and both are distinct from the positioning statement, which we’ll discuss in the next section.

The unique selling proposition is often the first bit of copy you’ll see above the fold on a given company’s homepage. It’s typically a single sentence-length headline, and is sometimes accompanied by a sub-headline. The essential word in the phrase is “unique.” The USP defines your position in the market insofar as it answers the question: What’s the ultimate point of differentiation between you and your competitors that makes your company the one worth doing business with?

Notice we said “point” and not “points.” There will be a single need or desire that your company’s offering will speak to most powerfully; the goal of your USP is to discover what that one thing is. In offering up this key selling point, you’ll immediately alert your prospects to why your business has the best offering out there, and why they should choose you over all other alternatives.

Keep in mind that your USP doesn’t have to revolve around a product detail (such as quality, features, or price). It can also call attention to a unique aspect of your business more broadly speaking (service, selection, speed, convenience, dependability, guarantees, customization, philanthropy, and so on). If you’ve been following along on our positioning journey, you’ve already spent some time considering brand differentiation, and you’ve got a sense of the variety of strategies you might use to emphasize your company’s “unique offer” here.

While the USP situates a business in relation to its competitors, the value proposition focuses more on how customers’ lives will be improved by working with the business. In other words, while a USP describes for your target market how you’re different, a value proposition answers the question: Why should they care about that difference?

Value propositions are longer statements than USPs because they express the tangible results or concrete outcomes (“benefits”) a customer experiences from using a company’s products or services. They serve to convince your target market they’ll get “value for their money” by describing exactly what that value is. The benefits can be both functional (the results of product features) and emotional (the positive feelings experienced when engaging with the product). The point is to show how those benefits outweigh the cost of the product or service. After all, “value” lives in the space between a consumer’s perception of the price and their impression of the benefits they’ll ultimately experience with the product.

Whereas you’ll likely shout out your USP above the fold of your homepage, you’ll place your value proposition either a little further down the page (since it goes into greater detail), or in the hero space of your landing pages or service pages. If you have more than one customer persona—or more than one product or service—you’ll have more than one value proposition; and you’ll want to ensure that each market segment sees the value that’s in it for them as they navigate your site.

Examples of USPs and Value Propositions

Let’s take Square as one example. The credit card processing company’s USP is “Start selling fast,” and it’s positioned just below the fold of their homepage. (Notice that Square’s USP speaks directly to its prospects: “You” is grammatically implied.) Square has chosen to focus on speed as their most important differentiating factor. Other homepage copy emphasizes this aspect of their business, promising that “with Square’s credit card processing, you can accept all major cards and get deposits as fast as the next business day”:

While their USP hinges on speed—a benefit relevant to Square’s entire target market—the company offers two distinct value propositions for two distinct market segments (“point of sale” and “retail”). Both are located further down Square’s homepage:

Clearly, the value propositions are more content-heavy than Square’s USP is. The USP “pops” in a headline sort of way: It’s short, catchy, memorable, and draws prospects in… though who those prospects are is a bit vague. The value propositions, on the other hand, list specific tasks customers will be able to accomplish and benefits they’ll experience by using Square’s product. In doing so, Square clarifies its personas for each product.

Square’s USP (speed) isn’t mentioned in either of its value propositions. What’s here is much more tangible, allowing prospects to envision the value they’ll get for their money.

Or consider the organizational app Evernote, whose USP—positioned in the hero space of their homepage—is “Feel organized without the effort.” Evernote includes a sub-headline that qualifies what they mean by “organization”—an inclusion that begins to clarify their target market. (They’re not offering to organize your closet, for example):

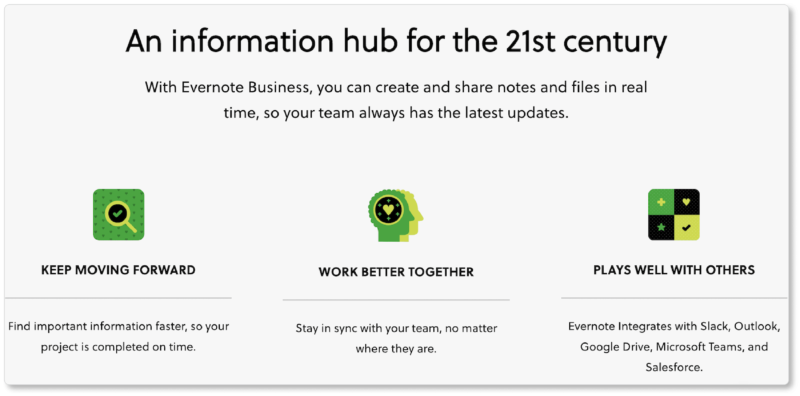

Evernote offers three separate plans (basic, premium, and business), and has a distinct value proposition—located on separate landing pages—for each. Here are the value propositions for their basic and business plans:

Both value propositions share a design: Evernote has chosen the three most significant benefits for each plan, and given each an icon for visual comprehension. But notice how different the headlines are from each other—despite the fact that they’re talking about the same product. The basic plan (“Remember everything”) is positioned for the individual looking for a digital version of the scrapbook, to organize and store notes and images for later (personal) access. The business plan, on the other hand, (“An information hub for the 21st century”) appeals to the persona looking for integration, collaboration, and the most current technology to facilitate teamwork.

Evernote’s USP speaks to—and draws in—both personas at once. The value propositions are where each visitor gets the details particular to their segment.

Creating a Unique Selling Proposition

The USP names the single most important differentiator between your business and every other competitor or alternative solution out there (including the alternative of not doing anything). As such, it wholly takes your competition into account. Take FedEx’s value proposition: “When it absolutely, positively has to be there overnight.” While FedEx doesn’t name its competition outright, the implication is that customers are gambling on on-time delivery with any other company—even those who promise overnight service.

Of course, there are plenty of overnight delivery companies who do deliver with consistent timeliness; but FedEx’s decision to position themselves as such makes them the clear choice for customers whose priority is speed. Of course, FedEx offers much more than overnight package delivery (they’ve got a whole suite of logistics services); but they chose one USP to create a core company identity with. No one thinks this is the only service FedEx offers.

Marketing Results positions itself more boldly against the competition. Here’s their USP:

The company introduces a radical distinction between themselves (the folks who “have it right”) and other digital marketing agencies, all of whom are focusing on the wrong metrics. Their USP shocks prospects into the possibility that any experience they’ve had with other marketing agencies has been a misguided waste of time and money.

All that’s to say you’ll be keeping your primary differentiator at the forefront of your mind as you draft your USP. Here’s one way to approach it:

- Describe your customer persona. A strong USP originates from an acute sense of who your target market is, what they want (both today and ultimately), and what motivates their purchase decisions. Be as specific as possible in defining your ideal customer.

- Describe the problem you solve. Articulating the solution you offer requires an intimate understanding of the need your target market is up against. What challenge are they staring in the face; and how does that showdown make them feel? How is it crippling their lives? Exactly how does your offering meet that need? What do their lives look like after your solution? How, specifically, are they improved?

- Identify your differentiators. List 3-5 of the most important benefits a customer gets from working with you that they wouldn’t get with your competitors. Product features, price, service, selection, speed, convenience, dependability, customization, philanthropy, warranties, and more are all up for grabs here. What makes you the irresistible choice?

- Determine your promise. The USP is fundamentally a promise, and it would behoove you to think of it as such. What’s the one beneficial thing your customers will experience with you… hands down, every time? Your promise may be implied rather than expressed in your USP; but it’s worth articulating to both yourself and your team.

- Combine, revise, and cut. Begin fashioning the above ideas into complete thoughts until you’ve said everything you want to say. Then cut, ruthlessly, until only one benefit and one differentiator remains. Remember, you’re aiming for two sentences max; so let go of anything that isn’t absolutely indispensable to what you want to say first to your prospects.

- Ask for feedback. Employees, colleagues, focus groups… ask anyone you can think of who knows your business and can give you intelligent, impartial feedback. Ask them if it meets the criteria for a killer USP (unique, memorable, believable). Be open-minded and patient with this process, no matter how many rewrites it requires. Your USP is worth getting just right.

Creating a Value Proposition

As you probably observed in the examples above, business value propositions tend to contain four main components:

- a headline. This is the attention-grabber that shouts out the primary benefit (typically not the same benefit the USP offers). Your primary benefit will be different for different segments.

- a sub-headline. The sub-headline is 1-2 sentences and explains the offering in more detail, more firmly connecting it with that segment’s primary pain point.

- a list of primary benefits. Naturally, you’ll need strong data about consumer motivations, desires, and pain points for this (and okay, every) section of your value proposition. What are the emotional and rational drivers of purchasing? What are their unarticulated needs? What benefits are most important to them, and how does your offering deliver those benefits? You know the questions to ask at this point; answer them here.

- an image. This might be a photo of the product, a graphic depicting its features, a hero shot that reinforces its primary benefits, and so on. You may even consider offering a video if your offering is complex enough—or unique enough—that it requires further explanation. (Try not to exceed two minutes here; you know how long the modern attention span is.)

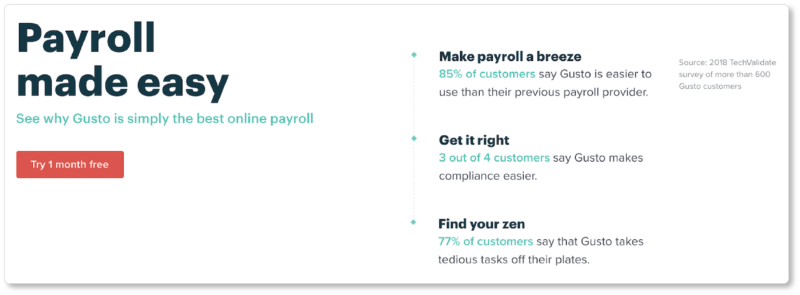

If you have them, insert concrete numbers into your sub-headline or benefit list, like Gusto does in the value proposition for its payroll platform. Statistics about the outcomes customers and clients received from working with you are invaluable here; they might be the social proof that finally prompts your more cautious prospects to click on that CTA. (Maybe you’ll even include a testimonial or two below your list of benefits):

You’ve probably noticed that design plays an important role in the value proposition. The image or video shows the benefits named (you want prospects to envision how your offering could affect their lives), while bullet points make for easy absorption. Don’t forget to speak directly to your prospect… and make sure that every detail you offer passes the “so what” test. Remember, you’ve already asserted your differentiator in your USP; here you’ll focus less on how you stand apart from the competition, and more on how your business can serve your prospects’ needs.

Granted, what we’ve offered you here are best practices… not every business will display their value proposition in precisely this way. Take a look at the websites of the strongest businesses in your industry and see how they’re offering theirs. Then take a look at the websites of business in vastly different industries, and see what you might draw from them in terms of presentation.

Testing the Strength of Your USP and Value Proposition

Before either of these statements go onto your website or into your marketing messages, your USP and value proposition have to pass a few tests. You’ll decide who’ll determine whether they “pass” or “fail”… but we suggest you invite some combination of employees, longstanding customers, colleagues, and anyone you know who has experience in marketing.

- The differentiation test: If your USP or VP could be positioned on any of your competitors’ websites and appear equally true of their offering, go back to the drawing board. You want to say something absolutely singular here. It’ll be well worth the labor involved once you discover that thing.

- The relevance test: If readers are still asking “so what?” after studying your statements, you haven’t spoken well enough to how your offering applies to their lives. Have participants ask you “so what?” ad nauseam, until you’ve dug deeply enough to touch the origin of the pain point. (This may signify itself as an “ah-ha” moment for them—which is when you’ll know you’ve hit upon the decisive place at which your offering intersects with their lives.)

- The believability test: If you’ve got statistical evidence in your VP, you’re on the right track here. Your customers should tell you whether your statements match their experience of doing business with your brand. Others should be able to tell you if they resonate with your general brand perception. Remember, while your USP and VP may be true, that doesn’t necessarily mean they’re believable. If you find yourself in this situation, consider what you’d need to add (or discard) to earn your prospects’ trust.

Pro tip: Establishing KPIs through which to measure your USP and value proposition ensure they’re claims you can prove down the road.

- The sustainability test. Your USP and VP are statements you should be able to defend and maintain indefinitely. If readers see attributes that aren’t sustainable, they should let you know. This includes benefits that could be easily replicated by future competitors or features likely to become “hygiene factors” as similar products come on the market. On the other hand, ensure that neither of these statements is limiting: Do they enable your business to grow without growing out of your USP and VP? (Of course, you can “freshen” these statements when necessary; but we generally wouldn’t advise radical changes.)

Finally, test variations of your USP and value proposition through A/B tests or by split-testing ads with significantly different benefits or language variations. Ultimately, your target market will determine what your “best” USP and VP are.

At this point, you’ve crafted most of your company’s internal and external branding documents: your mission, vision, and values statements; and your USP and value proposition. In the next section, we turn to that ultimate internal document: the brand positioning statement. We’ll give you templates, examples, and best practices to follow.